Since October 2023, the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division has opened two new pattern or practice investigations of municipal law enforcement agencies: the Trenton (N.J.) Police Department and the Lexington (Miss.) Police Department.

This brings the total number of active DOJ investigations of local and state police agencies to nine:

- Phoenix Police Department

- Mount Vernon (N.Y.) Police Department

- Louisiana State Police

- New York City Police Department’s Special Victims Division

- Worcester (Mass.) Police Department

- Oklahoma City Police Department

- Memphis (Tenn.) Police Department

- Trenton (N.J.) Police Department

- Lexington (Miss.) Police Department

In addition, DOJ has two other pattern or practice cases it is still working on despite having already issued lengthy Findings Reports: both the Louisville Metro Police Department and the Minneapolis Police Department are waiting for DOJ to put the finishing touches on the consent decrees both agencies already (prematurely and unwisely) agreed to here, and here.

So, the small number of attorneys and other staff within the DOJ Civil Rights Division’s Special Litigation Section / Police Practice Group seem to have their hands full, trying to juggle 11 separate cases.

And all of the above investigations were opened after April 2021.

Of course, this marks a historic expansion of DOJ’s own pattern or practice of taking control over local and state police agencies: in the 27 years prior to 2021, DOJ had only opened 70 total investigations of this type since Congress authorized them in 1994. That’s an average of around 2.6 investigations opened per year.

Now, with 11 such investigations opened within the past two and a half years, DOJ has nearly doubled that pace.

No wonder they are averaging more than two years of investigation per case.

Perhaps they have bitten off more than they can chew? Or is it a case of DOJ’s eyes being bigger than its stomach? Regardless of the cliche, DOJ’s appetite for involving itself in local police business has most definitely increased.

The DOJ reform machine’s hunger reached peak levels around 2013. Beginning that year, every new DOJ pattern or practice investigation of municipal, county and state police has ended with a consent decree, settlement agreement, or memorandum of agreement – each of them handing control of the police agency to DOJ itself or to a federal judge who will enforce DOJ’s reform mandates.

Although police consent decrees aren’t new (Pittsburgh got one in 1997), the past decade could be referred to as the Consent Decree Era, because DOJ’s investigations now always predictably end with a consent decree or similar signed agreement.

But one thing that is clear through 29 years of federal police reform crusading is that DOJ’s prescriptions for healing American law enforcement only make things in the cities they target worse. A lot worse.

Can the residents of Baltimore, Chicago, Seattle, Portland, Cleveland, New Orleans, Albuquerque, or Miami honestly say that their cities and police departments are better off after DOJ came in and imposed* its so-called “reforms” and “remedies”?

Those cities have all endured rising crime rates, tens to hundreds of millions of dollars frivolously wasted on ineffective but DOJ-mandated expenses, an exodus of experienced police officers and supervisors, and an inability to attract qualified people to join their police departments.

(*For the record, it is stipulated here that the leaders of those cities all fell for the DOJ sales pitch and VOLUNTARILY agreed to sign DOJ-composed consent decrees, settlement agreements, or memoranda of agreement, handing over control of their police departments to the federal government – more about that later.)

The facts about the ineffectiveness of DOJ consent decrees and the fraudulent nature of DOJ pattern or practice investigations are well-documented on sites like SavePhx.com and through the work of policing experts like Bob Scales, Travis Yates, and Jason Johnson. But one need not be an “expert” to see the truth; some quick self-study and research, even with mainstream sources, will quickly reveal the aforementioned high crime rates, bloated agency budgets, and crises in police recruiting and retention in DOJ-affected cities.

If a doctor claims he can heal you, but his remedies only make you sicker – that doctor might be selling bad medicine. A cure that is worse than the disease itself.

Such is the case with DOJ’s interventionist approach to “fixing” police agencies across the county.

None of this is to say that many, if not most, police agencies don’t have room to improve. Frankly, there are hundreds if not thousands of agencies throughout the nation that can be modernized and made more effective.

But DOJ has proven itself incapable of doing so through the use of consent decrees, with a nearly 30-year track record demonstrating exactly that. Maricopa County (Ariz.) Sheriff Paul Penzone announced October 2 that he is resigning, prior to completion of his second term, because of the ongoing burdens of DOJ and federal court oversight plaguing his agency since the Sheriff’s Office entered into a DOJ-composed settlement agreement in 2015, before he was elected. “I’ll be damned if I’ll do three terms under federal court oversight for a debt I never incurred and not be given a chance to serve this community in a manner that I could, if you’d take the other hand from being tied behind my back,” he said during a press conference.

Penzone claimed federal oversight and DOJ mandates have “depleted a considerable amount of resources in this office that could and should have been dedicated to public safety.”

“When I have more people investigating internal affairs and compliance issues than I do crimes in our community, something’s wrong,” Penzone said.

“It is absolutely true when I say the federal court oversight is more concerned about internal punishment than it is about external public safety, and that hurts the people of this community…You cannot have court orders that are solely focused on punishing an organization into oblivion and expect to make them better, versus incentivizing them.”

Insanity is doing the same thing over and over, in the face of failure, while expecting a different result each time.

So, with DOJ increasingly knocking on the doors of police agencies across the country, here is some advice for the city officials and police chiefs in those unfortunate places selected as the next victim of the pattern or practice charade:

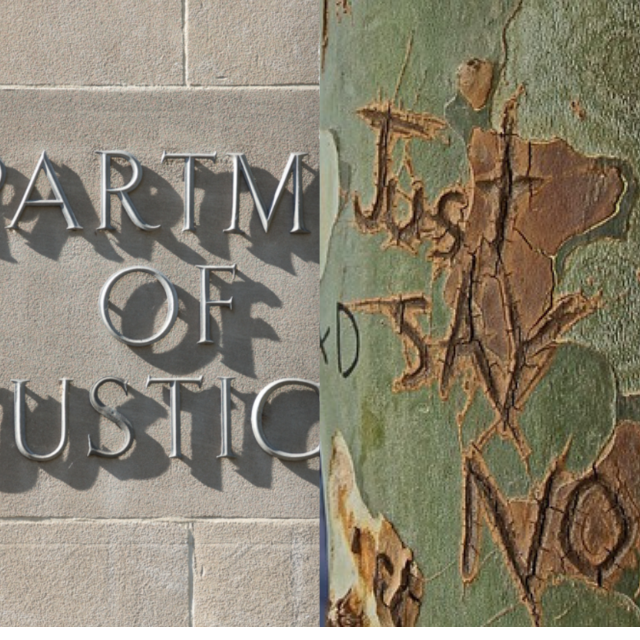

Just say no.

There is nothing within the scope of DOJ’s authority under federal law that gives it a right to access a local or state police agency’s internal records, reports, databases, or archives. DOJ has ZERO subpoena authority in police pattern or practice investigations under the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, 34 U.S.C. § 12601 or its predecessor 42 U.S.C. § 14141.

(DOJ and its allies tried to sneak that subpoena authority into law with the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act of 2021, but the bill failed in Congress. Not all heroes wear capes.)

And there is certainly nothing in DOJ’s statutory authority that gives it the right to physically access local police facilities or interview police officers.

It’s all voluntary. Every bit of it.

Usually, officials and chiefs meekly submit to DOJ demands for access, from the moment investigations are announced, out of fear or because it would “look bad” to do otherwise.

But it’s okay to say no. And in these cases, it can be much more beneficial than saying yes.

Case in point: Alamance County, North Carolina. In 2010, DOJ went to the Sheriff’s Office there and told Sheriff Terry Johnson that it was starting a pattern or practice investigation of his agency. DOJ alleged the Alamance County Sheriff’s Office was intentionally targeting Hispanic people for enforcement activity.

It was not.

Believing he had nothing to hide, Sheriff Johnson cooperated with DOJ and facilitated many of its requests for information and documents, as well as access to department facilities.

Team DOJ didn’t find anything.

However, that didn’t stop DOJ from releasing a “Findings Letter” declaring that it had still somehow managed to confirm all of its initial allegations of discriminatory and unconstitutional policing by the Alamance County Sheriff’s Office.

DOJ then asked Alamance County to voluntarily sign a consent decree – essentially, agreeing to DOJ’s baseless allegations and letting DOJ take control of the Sheriff’s Office for the foreseeable future.

Alamance County told DOJ “no”. Sheriff Johnson’s attorney advised DOJ officials to pound sand, and systemically refuted the allegations in the Findings Letter in a letter sent to the Civil Rights Division.

Never one to let facts stand in the way of an agenda, in 2012 DOJ still proceeded to file a civil lawsuit against the Sheriff’s Office in a U.S. District Court, alleging a pattern or practice of discriminatory policing by the agency, despite having no actual evidence showing that.

DOJ lost in court. Bigly.

In 2015, U.S. District Court Judge Thomas Schroeder wrote, summarizing his 253-page decision, “…after careful consideration, the court concludes that the Government has failed to demonstrate that ACSO has engaged in a pattern or practice of unconstitutional law enforcement against Hispanics in violation of § 14141.”

But what about DOJ’s earlier Findings Letter, which stated matter-of-factly that ACSO did engage in a pattern or practice of unconstitutional law enforcement? Despite losing in court and having its Findings Letter exposed as a fraud, DOJ simply moved on to the next police agency and used its same tried-and-true false tactics all over again.

Insanity.

Nowadays in the Consent Decree Era, DOJ’s standard operating procedure is to effectively use the illusion of authority, the mythology of federal supremacy, and the implicit threat of removal of federal funding to bully it’s way inside police agencies, where it then uses its permissive access to gather “evidence” to skew in a way that fits its preconceived narratives.

That dishonest practice of skewing the evidence is masterfully exposed by academic researchers Dr. John Paul Wright and Dr. Jukka Savolainen in their City Journal article, Maligning Minneapolis.

It’s long past time to end this scheme.

For those agencies that find themselves on DOJ’s naughty list in the future, you have the power to do just that. You hold all the cards, whether you know it or not.

Just say no.

Unless you actually believe that the agency you lead or represent is purposefully discriminating against minority communities or routinely and intentionally using unconstitutional excessive force – then by all means, say YES.

Otherwise, NO seems like a much better option after considering everything discussed previously.

But what about those agencies already lost in the fog of a current DOJ investigation? Those who said yes to the initial DOJ investigation but now have buyer’s remorse or serious hesitation about the consent decree already being written for them?

Is all hope lost? Are you destined to undergo the same fate as the Baltimores and Albuquerques that came before you, staring down the barrel of a consent decree?

Not quite.

That is, not unless you WANT to give DOJ full operational control of your department.

For just like the vampires in classic horror tales, DOJ cannot enter your house uninvited. DOJ sucking the life out of an agency can only occur with permission granted.

So to the local officials and police chiefs in those cities where DOJ is already conducting pattern or practice investigations – and we’re looking at you, Phoenix – the answer is the same.

Just say no.

See, the advice is consistent – just like DOJ’s track record of failures with police reform.

Just because DOJ has already breached the castle gates doesn’t mean you have to surrender the future and voluntarily agree to a consent decree or a memorandum of agreement.

An agency can – and should – say no when the offer of such an agreement is made. Remember, the ENTIRE PROCESS is voluntary.

DOJ has no real power here other than what it is freely given to it.

Why would a leader hand over his or her department to an entity that completely lacks any record of success?

Of course, if DOJ doesn’t like being told no, it can always choose to file a lawsuit to compel court-ordered reforms, just like it did in Alamance County.

And just like in Alamance County, DOJ would likely lose.

The standard in federal civil court requires a “preponderance of evidence” for a finding of responsibility. Simply put, that means DOJ must prove in court that it is more likely than not that its allegations of discriminatory and unconstitutional policing are true.

So, call DOJ’s bluff. And make DOJ prove its case.

If the allegations are true, and proven, DOJ would prevail in court.

And your agency would then end up with the exact same mandates imposed that you would have agreed to in the form of a consent decree.

But why would you sign a plea bargain if you’re not guilty – and before charges are even filed? Admitting to guilt where it doesn’t exist? That’s like snatching defeat from the jaws of victory.

DOJ attorneys are unlikely to prevail in court with a pattern or practice lawsuit, and they know it. That’s why they rely almost entirely on intimidation and coerced “voluntary” agreements to avoid courtrooms at almost any cost.

So, just say no.

Yes, DOJ will have its friends in the media say mean things about your agency.

But those mean things will still be said even if you sell your agency’s soul for an easy way out.

Nobody ever said being a police chief or an elected official would be easy.

There can be disagreement on methods, but not on facts. The DOJ consent decree model of police reform is a failed concept.

The Consent Decree Era must end. So, just say no.

None of this is to imply that reforms aren’t necessary at police departments – even at the Phoenix Police Department, which is often called upon by other police agencies that want to learn how to implement best practices in topics ranging from deployment of new less-lethal systems to crisis intervention tactics.

Phoenix PD recently self-initiated a total overhaul of its use of force policies, along with a multitude of other national best-practice initiatives. Interim Police Chief Michael Sullivan has spoken publicly about it many times.

You can even go to a Phoenix PD website and read the new use of force policy (it’s in the folder called “Policies Under Review”). The policy is good. Not that its previous policy was bad or insufficient – you can read that one, too – but the new one is updated, more comprehensive, and appears to be organized to be more accessible.

Additionally, just this year, Phoenix PD received a prestigious organizational accreditation through the voluntary Arizona Law Enforcement Accreditation Program (ALEAP), which is awarded by the Arizona Association of Chiefs of Police. The accreditation process took two years and measured 175 separate standards – including policy, practices, procedures, management, operations, and support services. Interim Chief Sullivan spoke at the award ceremony and said, “When it comes down to it, accreditation is about improving overall performance and making sure we are in compliance with proven national standards and best practices.”

I wonder if the Arizona Association of Chiefs of Police is in the business of certifying police departments that engage patterns or practices of discriminatory and unconstitutional policing?

The notion that Phoenix PD needs DOJ to dictate how to improve its policies is absurd.

What’s even more absurd is what DOJ will most likely say about Phoenix PD in its impending Findings Report – that just like in Louisville and Minneapolis, it has “reasonable cause” to believe Phoenix PD engages in a pattern or practice of discriminatory and unconstitutional policing.

DOJ must forget that it has already defined what “pattern or practice” means – it would be saying that Phoenix PD has an established organizational practice of discriminatory and unconstitutional policing, repeatedly and over a lengthy period of time.

That’s not true, and DOJ knows it. That’s why it wants Phoenix to voluntarily sign a consent decree or memorandum of agreement – to bypass having to prove what are likely to be outrageously false allegations.

So, just say no.

Of course, even Phoenix PD can – and should – do better. Every police agency must be committed to the concept of never-ending organizational improvement.

Phoenix officials may be hesitant to admit it, but there must certainly be aspects of its operations and policies that can be made more effective.

But they shouldn’t hesitate to say it – admitting organizational shortcomings and working with the local community to craft best-practice policies is the future of policing.

This Is The Way.

It isn’t an embarrassment to want to do better – it’s courageous and transparent leadership.

And it doesn’t need to involve counterproductive signed federal agreements that hand over the organization’s keys and total departmental control to DOJ.

Improving your agency doesn’t need to involve consent decrees or memoranda of agreement.

Phoenix should remember this in the coming weeks and months – and leaders in cities yet to be affected by the DOJ police reform circus should remember it forever.

If DOJ is serious about police reform in Phoenix (and elsewhere), it should blow the dust off of one its own old tools – the concept of technical assistance.

Once upon a time – as recently as 11 years ago, prior to the Consent Decree Era – the DOJ Civil Rights Division sent technical assistance letters or technical assistance reports to agencies it investigated, offering suggestions on how to improve policies without trying to take over the agency or install an “independent” compliance monitor who used to be a DOJ minion.

Now relegated to the dustbin of history, technical assistance as part of DOJ investigations has given way to policy mandates, required spending and surrender of agency control as DOJ ushered in the Consent Decree Era a decade ago.

With a return to technical assistance, DOJ could abandon its ineffective consent decree mandates and instead offer to partner with Phoenix on reforms – in areas where reforms are not already underway.

And Phoenix could double down on its status of being a “self-assessing, self-correcting” department, as Interim Chief Sullivan has publicly declared, by evaluating DOJ’s technical assistance suggestions in earnest and applying that advice where it makes sense (and declining it where it doesn’t).

If DOJ refuses to pivot to technical assistance instead of signed agreements, Phoenix should simply move forward without DOJ, while immediately turning off DOJ’s access to Phoenix PD records and materials.

What would DOJ do if Phoenix really does say no? Nobody knows. But most importantly, it doesn’t really matter. The City of Phoenix doesn’t answer to the U.S. Department of Justice – at least, not yet.

Maybe DOJ would file a pattern or practice lawsuit that Phoenix would need to defend itself against. Then again, maybe it wouldn’t.

Instead of worrying about that, Phoenix should accelerate its own internal reform efforts – and talk about it. A little bit of honest and proactive communication with Phoenix residents about why a signed DOJ agreement isn’t necessary there would go a long way towards building trust and heading off some of the bad publicity DOJ could orchestrate after being rendered obsolete.

Phoenix could also independently partner with any number of non-governmental organizations – such as the Police Executive Research Forum’s Center for Management and Technical Assistance, the National Policing Institute, or the Center For Evidence-Based Crime Policy at George Mason University – instead of DOJ, as a public demonstration of its commitment to improving policy and accountability in the most effective and transparent ways possible.

No matter what they are told by DOJ or its allies, it is critical for Phoenix leaders to remember that the ultimate responsibility for the success or failure of Phoenix PD policy rests with the City Council, city executives, and the Police Chief – not with DOJ or outside consultants.

When DOJ takes over a law enforcement agency with a signed agreement, the community in that city, county or state loses the ability to hold local leaders accountable for phenomena like rising violent crime. With unnamed and unaccountable DOJ officials in Washington DC making decisions about what a police department can or cannot do, and determining agency policy, citizens lose their local voices in the process.

That is unacceptable.

After 27 months (and counting) of watching and waiting, those same city leaders in Phoenix should open a dialogue with the community there and share their thoughts on exactly which direction the city intends to go regarding its DOJ investigation.

To date, only one Phoenix leader has done that – Councilwoman Ann O’Brien.

On November 17, Councilwoman O’Brien published an opinion piece in the Arizona Republic and boldly declared that she will not support a DOJ consent decree in Phoenix. More importantly, she explained WHY she won’t support a DOJ consent decree in Phoenix.

She is the only Phoenix official so far to do so.

Her colleagues on the City Council, at City Hall, and in the Police Department should not let her stand alone.

Together, they can ALL say no – and explain to their community that police accountability works best when it stays local.

That isn’t controversial.

Or better yet, in addition to saying NO to a signed DOJ agreement, Councilwoman O’Brien and her colleagues could also open a dialogue with DOJ and let it know that while there will never be a consent decree or a memorandum of agreement in the City of Phoenix, city leaders there are more than willing to hear what DOJ has to say in the form of technical assistance, and to partner with DOJ wherever it makes sense for the unique needs of the Phoenix community, while reserving the right to say “no” anytime a DOJ suggestion would not be a good fit, based on reliable data and careful review.

But Phoenix leaders like Interim Chief Sullivan, Mayor Kate Gallego, City Manager Jeff Barton and Councilwoman O’Brien will remain in charge, and accountable.

Not DOJ or its coterie of judges and monitors.

Finally, someone is in a position to put a stop to DOJ’s pattern or practice of ineffective police reform.

And it’s well past time to put a stake through the heart of the DOJ Consent Decree Era, to end it once and for all.

We’re looking at you, Phoenix.